👋 Hi, welcome to Till’s Newsletter, a weekly column all about AI for the AI-avoidant. Let’s learn together.

5 Min Read

Happy Thursday folks :) In today’s newsletter …

🙋🏼♂️ Human-centered design: Building for when shit hits the fan.

🚫 You’re not a bonehead, some things are just hard to use.

◼️ Human-centered AI and the “black-box effect”.

“When we collaborate with machines, it is people who must do all the accommodation. Why shouldn’t the machine be more friendly?”

– Don Norman, The Design of Everyday Things

Last week, I wrote to you about how we talk to AI. We went into prompting techniques – specific ways to shape and reshape your requests so you can make yourself clear to the AI you’re working with.

But that begs the question: Is the onus of being understood really always on us?

We’re told that in any good relationship, communication has to be a two-way street. So what are we doing to make sure that the technology built to work alongside humanity is built … with humanity in mind?

Around this time last year, I picked up The Design of Everyday Things by Don Norman – a man I’d never heard of, but who would quickly make me rethink my relationship to the tech I use everyday.

*Don Norman, by the way, is a design legend “now busily engaged in his 5th retirement,” according to his LinkedIn profile. Like I said, a legend.

In his book, Norman advocates for Human Centered Design (HCD), which I’ll take a stab at defining in my own words here.

HCD is tailored to real life, taking into account how people actually do something vs. how they “should” be doing it, all in an effort to design things real people love to use.

It’s design with the ever-present acknowledgment that there isn’t always a correlation between the best solution in theory and the best solution in practice – often because people will always do what they do best: behave inconsistently, make mistakes, and dump the instruction manual.

☕️ A simple example: This cup with a quirky handle, made by a guy I met at a networking event recently. After deciding that mug handles weren’t made with human hands in mind, he got to work and reimagined what the experience of holding a mug could be like.

Next time technology’s got you stuck, try giving yourself the benefit of the doubt.

Can’t figure out how to turn that new device on? Maybe the “on” button is just stupidly hard to find.

Did you have to watch 2 1/2 YouTube videos to figure out how to use that new feature? Well maybe the feature wasn’t intuitive.

Maybe you’re not a (complete) bonehead. Maybe the thing you’re struggling with just needed to be built more intuitively.

“The idea that a person is at fault when something goes wrong is deeply entrenched in society … But in my experience, human error usually is a result of poor design: it should be called system error.”

– Don Norman, The Design of Everyday Things

To understand how to work alongside AI, we’ve got to overcome “the blackbox effect”.

Human-Centered AI (HCAI) is the AI-world equivalent of HCD, and it’s more important than ever today.

In his 2019 article on HCAI, author Wei Xu describes the incomprehensibility and mystery of AI to the general public as the “black-box effect”.

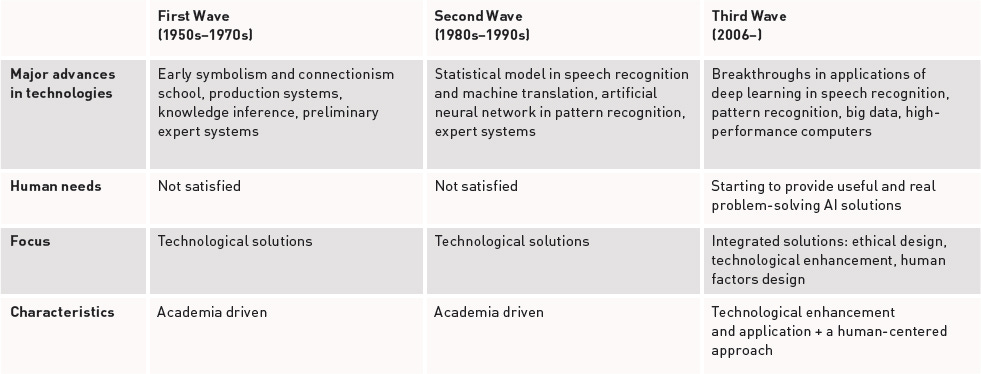

Much like the rise of computers in the 80s, Xu writes, AI experts started off designing only for other experts in mind, creating a wide-spread accessibility problem for the technology.

Especially in early days, lack of transparency is a big issue for technology as impactful as the computer, let alone AI.

It’s in the early days that foundations are laid, and the answer to the question of who is laying those foundations – and with who in mind – can have an outsized impact.

In the case of AI, the impact of that opaqueness in the industry can manifest as racial and gender biases in AI face-recognition technology or, as Xu illustrates, a medical-diagnostic AI indicating that a patient may be predisposed to cancer without actually being able to explain to either the patient or the doctor how it got to that concerning conclusion (imagine how frustrating that would be ! ).

AI can’t just be compatible, it has to be companionable.

“I’m interested in when and where and if AI might just be more than compatible but maybe actively companionable ; might extend and elevate creativity the way a pen, or a paintbrush, or a musical instrument can.”

– Michele Elam, HAI Associate Director at Stanford HAI.

The challenge with HCAI is that AI can’t just be compatible with humanity, it has to act as a well-meaning and effective companion as well. AI systems have the potential to automate many processes now carried out by humans, making their roles obsolete, something both Xu and IBM agree can’t happen.

AI experts at IBM believe that HCAI-focused collaboration between AI and humans should free the human up for high-level creativity, goal setting, and steering the project, while AI can augment the abilities of a human being to pitch in creatively, scale potential solutions, and handle low-level detail work.

Like I wrote in my first newsletter, the hope of AI is that it becomes a collaborator, not a replacement. To do so, we’ve got to understand one another, and that road runs two ways.